We’ve all heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect. It can be seen every day. When Donald Trump claimed he knew more about ISIS than the military. When Joe Biden gave advice on how to properly use a shotgun. When Elon Musk spreads easily refuted conspiracy theories. When Congress holds literally any hearing having to do with tech. We constantly see illustrations about how people being supremely confident of things they know nothing about, as clearly evidenced by the following graph demonstrating the results of the research of David Dunning and Justin Kruger.

Or do we? You know what would be really ironic? If this actually wasn’t the Dunning Kruger effect. If everyone confidently explaining every dumb thing a politician or tech billionaire said by completely misrepresenting this cognitive bias. That would be peak Dunning-Kruger right there. That would be Dan Quayle spelling “potatoe” level Dunning-Kruger.

Well, I’ve got some bad news.

The above chart doesn’t demonstrate the Dunning-Kruger effect. This demonstrates the Dunning-Kruger effect.

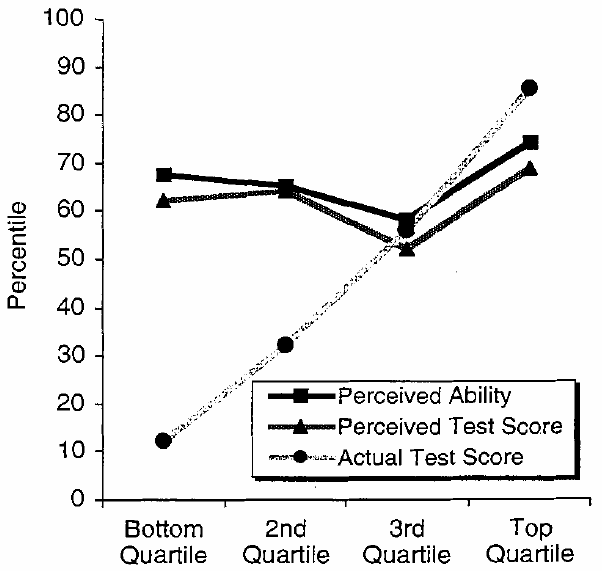

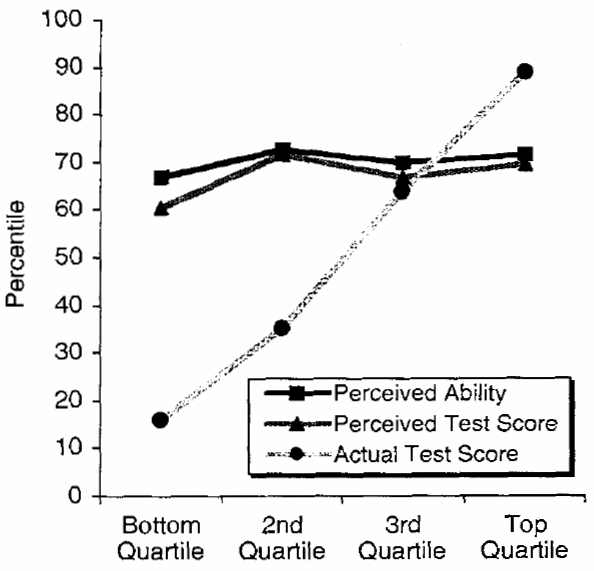

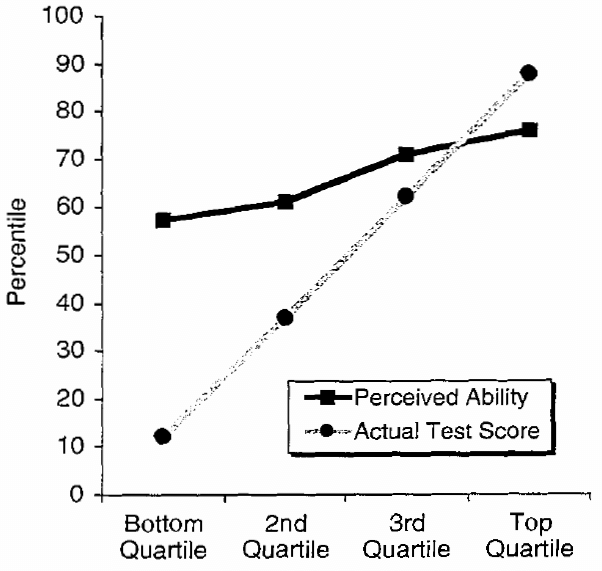

You can read the paper here. The researchers gave the subjects (undergraduate students at Cornell) assessments in humor, grammar, and logical reasoning and judged both how the actual scores and how the students thought they did.

People who have lower competence do tend to overestimate their ability. And people with higher competence do tend to underestimate their ability. But not to the point demonstrated in the above cartoon. There is no “Mount Stupid” or “Valley of Despair”. As people gain competence they tend to gain confidence. Just not as much as expected.

Really the only study which even approaches the cartoon version of Dunning Kruger is the logical reasoning study, which used questions taken from an LSAT test preparation guide. Here we do see some drop in confidence as the subjects were more competent, but nowhere near as pronounced in the cartoon. Everyone just sees themselves as having performed in the 50-75th percentiles, which of course cannot be true.

The grammar study was similar. The perceived test score percentiles for all four quartiles was in in the 60s.

In both these studies, it is important to remember that the participants were undergraduates at a prestigious university. That means that it’s not entirely unreasonable that they thought of themselves as being in the mid upper percentiles. If compared to the population as a whole, they would probably all be well above the national average. But instead they are being compared to other Cornell undergraduates (remember these are being scored by percentile, not raw scores).

However I’m guessing that would be less likely with the humor study. I don’t know of any reason to think Cornell students are particularly funny, but me let me know if I am missing something. And in that study we see a more consistent rise of perceived ability compared to actual ability.

Part of this is just a classic regression to the mean. People tend to estimate their abilities closer to the middle value. And it kind of has to. Someone who did poorly has much more room to err in thinking they did better than they did. If you got every answer wrong, you couldn’t have thought you did worse than you actually did. And vice versa with the competent people.

That’s not all of it of course. If it were, the graph would be symmetric, while clearly the overestimation by the incompetent is more than the underestimation by the competent. But that can be easily explained by the more competent being able to more accurately predict how well they did. To quote from the paper, “We propose that those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it.“

In short, Donald Trump isn’t the living embodiment of the Dunning-Kruger effect. We all are.

A very interesting read. Relevant to many aspects including job interviews. How to easily distinguish/rank candidates on actual competence versus self-perceived competence.